Rethinking the fable of “the Tortoise and the Hare” involves conducting field observations, interviews, and museum visits (along with reading a lot of popular and scientific material). I do this work to gather together the ecologically true stories of these animals.

My motivation derives in large part from results of a recent sobering study: books featuring talking animals skew readers’ understandings of basic biological principles and lead to children explaining wild animal behavior in terms of human motives and emotions (1; Ganea et al 2014; ).

Desert tortoises I sketched in Phoenix, AZ (c), B.G.Merkle, 2016.

Furthermore, according to recent reports from the Pew Institute, scientists consider their work essential for public discourse, and the majority of the public wants more media coverage and more access to this information in public settings and in k-12 education. I take this information to heart as an interdisciplinary science communicator – people don’t understand how ecosystems work, but they want to. To counteract this issue, I want to transform a familiar fable into a portal.

Doing so requires visiting the locations on earth where tortoises and hares co-exist. I’ve chosen to focus on three ecosystems where Aesop’s popular fable could actually play out – the Sonoran Desert (specifically Arizona), Kenya, and the Mediterranean region of southern France.

I am exploring, documenting, and incorporating the animals, their ecosystems, and the people who live in these regions, into a manuscript which tells the deeper story of these places, the scientists focused on them, and the diversity of habitats and species involved with the actual ecology of the tortoise and the hare. This combination of fable, science, and art will provide the public with an accessible and engaging gateway into complex ecological systems and research efforts.

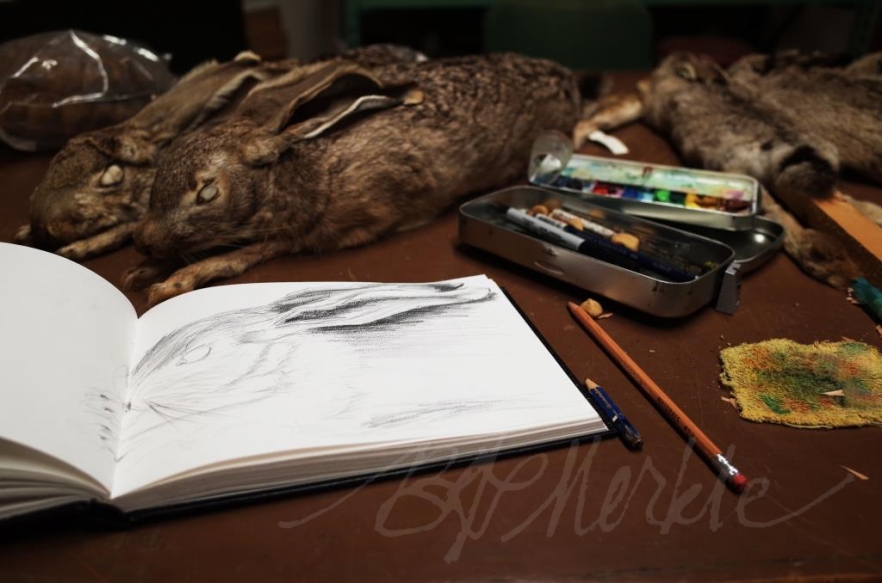

A black-tailed jackrabbit (yes, jackrabbits are technically hares) specimen I sketched while visiting the University of Arizona’s Vertebrate Museum. (c) BGMerkle, 2016.

Currently, this project is focused on the species in three places (Arizona, France, and Kenya). Those species are:

Tortoises:

- Bell’s hinge-back Tortoise (Kinixys belliana Gray): IUCN/SCC status Not Listed/Least Concern (1996)

- Desert Tortoise (Gopherus agassizii Cooper): IUCN/SCC status Vulnerable

- Herman’s Tortoise (Testudo hermanni Gmelin): IUCN/SCC status Near-Threatened

- Leopard Tortoise (Stigmochelys paradalis Bell): IUCN/SCC status Not Listed/Least Concern (1996)

- Pancake Tortoise (Malacochersus tornieri Siebenrock): IUCN/SCC status Vulnerable

- Speke’s Hinge-back Tortoise (Kinixys spekii Gray): IUCN/SCC status Not Evaluated

- Spur-thighed Tortoise (Testudo graeca Linnaeus): IUCN/SCC status Vulnerable

- Western Herman’s Tortoise (Testudo h. hermanni Gmelin): yes, a distinct subspecies; IUCN/SCC status Endangered

Desert Tortoises sunning themselves on a warm December afternoon at the Phoenix Herpetological Society Sanctuary. (c) BGMerkle, 2015

According to the most recent assessment of chelonian biodiversity and conservation status, conducted by the IUCN/SSC Tortoise and Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group, there are at least 192 tortoise species still alive – 11 species/subspecies have gone extinct since 1735 (Rhodin et al 2010).

While this might seem like a fairly hearty ratio, the report authors mince no words in their abstract: “…of the 328 total species of turtles and tortoises, 156 (47.6%) are Threatened, with 90 (27.4%) Critically Endangered or Endangered. If we adjust for predicted threat rates of Data Deficient species, then 54% of all Turtles are Threatened. If we include Extinct in the Wild and Extinct species, then 50.3% of all modern turtles and tortoises are either already extinct or threatened with extinction. Turtles are among the most endangered of any of the major groups of vertebrates, more than birds, mammals, cartilaginous fishes, or amphibians” (Rhodin et al 2010).

A careful reading of the report indicates at least 52 tortoise species are Near-Threatened, Vulnerable, or worse (8 Endangered, 8 more Critically Endangered, 2 Extinct in the wild).

This grim set of statistics has particular relevance to my project – several of the tortoise species I am interested in observing in their native ecosystems are listed by the IUCN. Furthermore, with Charles Darwin and Galapagos tortoises inextricably linked, tortoises in and of themselves present an extraordinary opportunity to communicate about biodiversity.

Sketching hare specimens at the University of Arizona Vertebrate Museum. (c) BGMerkle, 2016

Hares:

- Antelope Jackrabbit (Lepus alleni)

- Black-tailed Jackrabbit (Lepus californicus)

- Cape Hare (Lepus capensis)

- Ethiopian Hare (Lepus fagani)

- Ethiopian Highland Hare (Lepus starcki)

- European/Brown Hare (Lepus europaeus)

- and a remote possibility of seeing the Abyssinian hare (Lepus habessinicus)

In contrast to the extensive research which has been conducted on tortoises, the IUCN/SSC Lagomorph Specialist Group, in the introduction to their 1990 report on rabbits, pikas, and hares, concedes, “Lagomorphs are relatively small mammals and do not excite the curiosity and appeal of some of their larger kind. There has thus never been much financial support for conservation. But they are of critical importance in world ecosystems” as they make up the base of many food chains (Chapman and Flux 1990).

Long a vivid, mythical, allegorical, and sometimes bizarre creature, depending on cultural attitudes, hares are widespread and successful, ecologically speaking. Among the hares (sometimes known as jackrabbits), 13 of 29 species are rare, uncommon, or endangered, and Chapman and Flux matter-of-factly note, “Far more information is needed on the taxonomy and distribution of hares before clear conservation priorities can be established.” (1990).

The general dearth of data holds true for the hares in at least two of my proposed field sites – ecologists working in Arizona and Kenya have confirmed to me that limited study has been done on the hares in these regions, aside from the Black-tailed Jackrabbit in the American Southwest.

While I do not propose to remedy the lack of scientific attention given hares, this project will at least increase public awareness of their still-to-be-studied biodiversity.

How can you contribute?

I am looking for the following, and would greatly appreciate your support:

- Contact information for tortoise and hare ecologists, particularly those studying the species that occur in Arizona, France, and Kenya.

- Scientific or popular materials about either species.

- Financial support: traveling to Kenya and France is a pivotal component of this project. It won’t be a vacation – I’ll be working every waking minute in these locations to capitalize on what might be a single opportunity to visit them, connect with these species in their native environments, and observe scientists working in these regions.

This project would not be possible without support from:

Maria Altemus, Crystie Baker and the team at the Phoenix Herpetological Society, Melanie Bucci at the University of Arizona Museum of Natural History’s Vertebrate Collection, Jonathan and Akiko Derbridge, Kirk Emerson and Ron Wrighty, Jake Goheen, Alyson Hagy, Mark Jenkins, Jeffrey Lockwood, Jerod Merkle, Tom Morrison, Elizabeth Womack at the University of Wyoming’s Vertebrate Museum